A Moment Infused with Meaning: Holocaust Survivor Visits Campus on International Holocaust Remembrance Day

Prior to the German occupation of Vienna, Dr. Eric Ungar (b.1926) was aware of no threat to European Jews. In grade school, when some fellow students turned up in Hitler uniforms, it had little effect on him. At age 10, he enrolled in technical college (equivalent to American preparatory high school); after a year there, Jewish students were expelled and sent to an ordinary high school. A second dismissal, this time to a special Jewish school, led to a stark understanding among Ungar and his peers: “We slowly realized that a concentration of Jewish kids was not a good idea, so we stayed at home.” As the annexation of Austria loomed, Ungar’s father moved the family from their apartment in Leopoldstadt—a largely Jewish district—to the city center. One day, while Ungar was in the back room of his father’s store studying, a man came into the shop wearing a Nazi uniform; he demanded the store keys and money before declaring, I’m in charge now. In a moment, their livelihood was taken from them. When rationing began, extra provisions from the neighborhood butcher and dairy—given in secret to augment the significantly smaller rations allotted to Jews when compared with non-Jews—helped the family to survive what was becoming an untenable situation.

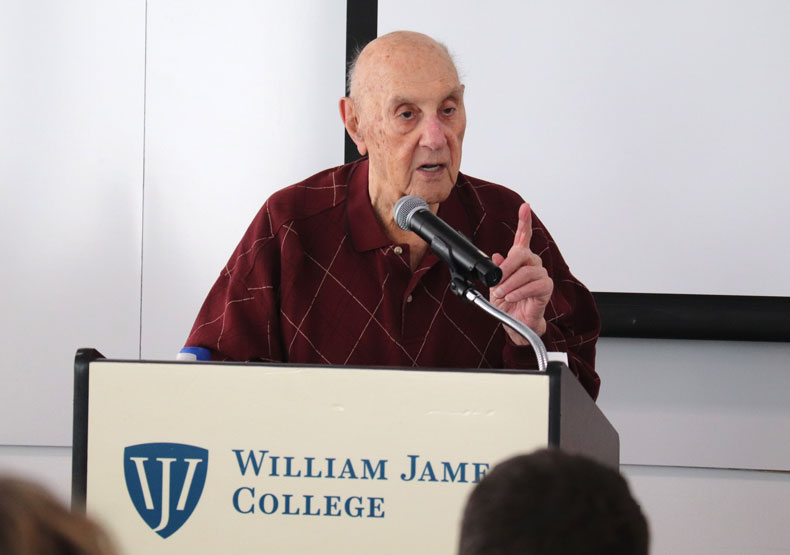

“It became fairly clear that there was no future for us in Vienna, so we looked at how to get out,” says Ungar, who visited the William James College campus on Monday, January 27 to share a sliver of his family’s story with an audience including Operations Coordinator for the Dean of Students Office, Melissa Lane, his granddaughter. Established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2005, International Holocaust Remembrance Day commemorates the 1945 liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau and honors the memory of the six million European Jews who died during World War II—among them Dr. Ungar’s maternal grandparents; two aunts and an uncle on his father’s side; and countless friends. (His paternal grandparents had died before Germany annexed Austria.)

“In order to emigrate anywhere, we had to have documentation,” says Ungar, nodding to the most difficult piece of the puzzle to secure: An affidavit from someone in the United States willing to sponsor the family and ensure they would not be an economic burden. “Of course this was not easy to obtain,” says Ungar who recalls his father getting hold of a New York City phone book and writing to everyone with their surname saying, We’re probably not related, but can you help us? When this avenue did not pan out (the one man who offered to help did not have adequate resources to be accepted by the State Department ), an aunt who was already living in the Bronx set out to find a guarantor by visiting every synagogue she could find and sharing her Viennese family’s plight with each congregation. After several Saturdays in a row, one man stood up and said: Where do I sign?

“He gave us an affidavit and saved our lives” says Ungar of the auspicious timing. Shortly before his 13th birthday, the family received notice to report to a collection station the following week for transport to a concentration camp. The only exception, save for being deathly ill, was to have all the necessary documents needed for travel.

“Just in the nick of time, we had everything together,” says Ungar who left for the United States—first via train to Antwerp, then via ship to New York—in November 1939; he was 12 years old.

Shortly after their arrival, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (established in 1881 to help Jewish immigrants fleeing antisemitism and violence in Russia and Eastern Europe) decided a concentration of Jews in New York City was not a good idea—so they arranged to relocate the Ungars to the Midwest.

“They sent us to Cincinnati, except we got the wrong tickets and wound up in St. Louis,” says Ungar of what turned out to be good fortune: It’s where he was able to study and eventually meet his future wife, Goldie. Ungar returned to school and realized he was “a pretty good student.” He finished grade school, went to high school, was motivated, took extra courses, and graduated at the top of his class. Washington University in St. Louis had the very enlightened policy to provide scholarships to top graduates of local public high schools, and Ungar secured one.

“There was no way my parents could afford to send me to college,” says Ungar, recalling one of many godsends he received along the way. After a year of studies and good grades, Ungar turned 18 and received a draft card.

“War was raging in Europe,” says Ungar who, upon reporting to the draft board, learned his non-citizen status made him ineligible for service—so he volunteered. Halfway through basic training at Fort Bliss, he was sent to Belton, Texas and sworn in as an American citizen. He went on to attend Officer Candidate School and emerged as a 2nd lieutenant, tasked with teaching young soldiers how to fight. Halfway through preparation for deployment to Asia, the Germans surrendered. Soon after, Ungar found a notice on a bulletin board seeking military volunteers to go to Europe.

“Since German was my first language, I was accepted,” says Ungar who soon found himself in Bremen as part of the Graves Registration Command, tasked with finding and identifying American dead. His later assignment on German soil was in Berlin, during the Cold War, where Ungar was responsible for a team that regularly entered the Russian Zone, via Checkpoint Charlie, looking for more dead and their stories—one of which has stayed with him to this day.

While talking with the caretaker of a small-town cemetery, Ungar learned that an American plane had been shot down, leaving four airmen to descend via parachute. While three of them were returned to the militia by locals, the fourth was killed.

“Because he looked Jewish,” recalls Ungar of the caretaker’s attitude toward the fourth man they murdered, as if they’d killed a bug.

Amidst Ungar’s many adventures, he recalls rummaging through the attic of a half-destroyed villa in Bremen and finding a copy of Mein Kampf which he first read and then gleefully burned.

“Hitler, evidently, was a great organizer who took the disaffected German rabble and made it into a political party,” recalls the former infantry officer who witnessed the atrocities that occurred when the government was taken over by force in order to “make Germany great again” after the war.

“I made my peace with [the Germans] by becoming friends with many of them,” says Ungar of the everyday people he encountered working hard to support their families, earn a reasonable living, and make progress following the war.

“Turns out, they were not all monsters,” he says, adding, “I have collaborated with several Germans in my technical work and even co-published a book with them.”

Ungar returned to Vienna several times, including once when he was stationed in Berlin. As to what he found? “The city was partially ruined, [and] the area where the synagogues were was destroyed except for one, but it still felt like home,” he said, adding that he remembered every street and shop--including where to get the best pastries. The Jewish community was still there and, on subsequent visits, he was surprised to find it growing and thriving.

In 1998, Ungar donated the Ungar Family Papers—consisting of correspondence the Ungar family received from those who could not leave Vienna and were ultimately sent to concentration camps—to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum where they remain part of the online collection.

At the event’s conclusion, Dr. Ungar was called upon for advice on moving forward, given the current state of our country and the world—both of which remain divided by differences.

“That is a very good question and, I have to tell you in all honesty, I don’t have any answers,” said the 98-year-old Ungar who added: “It's very hard, when the world feels fractured, but people have to respect each other [despite] opposing needs and desires and ambitions. It’s very hard to reconcile everything. I would love to see something positive happen in my lifetime, but it’s a lot to expect.”

NOTE: Director of Student Life & Student Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion Meredith Apfelbaum shared the following remarks in her introduction: During a career spanning more than seven decades, Dr. Eric Ungar—a renowned engineering scientist, a U.S. military veteran, and a Holocaust survivor—left a profound mark on the field of vibration and noise control engineering. He has published over 300 scholarly papers and received 24 honors and awards from organizations including the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and the Acoustical Society of America, among others. Dr. Ungar's work includes multiple projects having to do with vibration in buildings, laboratories, transportation systems, medical devices, space systems, astronomic observatories, military aircraft, and seismic measuring equipment that astronauts took to the moon—just to name a few.

- Tags:

- Around Campus

Topics/Tags

Follow William James College

Media Contact

- Katie O'Hare

- Senior Director of Marketing

- katie_ohare@williamjames.edu

- 617-564-9389